There are historical instances in Cape Town, such as the 1901 bubonic plague, where sport, disease and injustice were entwined. This plague resonates with current situations. Pandemic disasters result from social developments that happened before the outbreak itself, leaving a scar on society long afterwards. During pandemics, medical interventions are justifiably foregrounded. However, pandemics also have non-medical impacts such as the creation of stigmas. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, such stigmatisation led to health legislation that aimed to ‘preserve the purity of the white race’ in Australia or created segregated societies such as in the southern part of America.

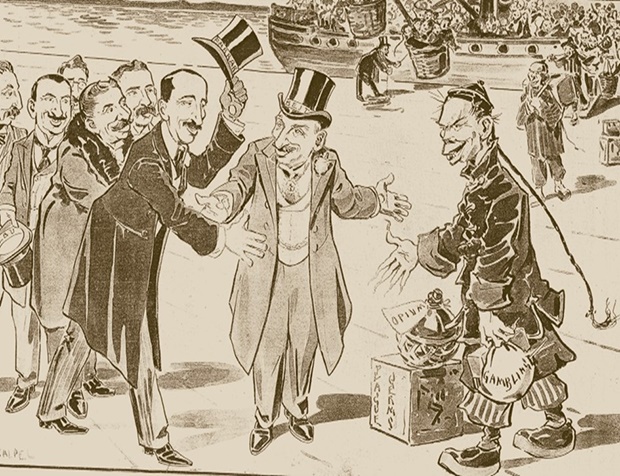

The history of sport in Cape Town proves to be a powerful metaphor in furthering the creation of stigmas that informed legislation. Historical records reveal how the city dealt with plagues in the past, particularly those located on the social and cultural outer edges of society. Since colonisation, city officials endeavoured to ‘other’ anybody that did not meet European ‘civilisation’ standards. ‘Civilisation’, in the colonial sense, included sanctioned sport. At the turn of the 20th century, Chinese immigrants were singled out directly for this type of treatment which was termed the age of the ‘yellow peril’. The media portrayed gambling, crime and sexual indecency as peculiarly Chinese. Not surprisingly, one South African newspaper called for “co-operation to keep that plague (the Chinese) from our country”. Quite correctly, one Chinese writer wrote in a local newspaper about the unfairness of criminalising fah-fee (Chinese gambling) while the city referred to horse-racing as the Kings Sport.

What followed was a host of satirical weeklies that served the chauvinistic interests of the lower- and upper-middle classes, who often used outrageously racist stereotyping to denigrate Chinese people. We could jump a century forward and say this racial, if not xenophobic reference, is akin to certain modern-day leaders and ordinary citizens blaming the Chinese nation, as a whole, for the spread of the Covid-19 virus.

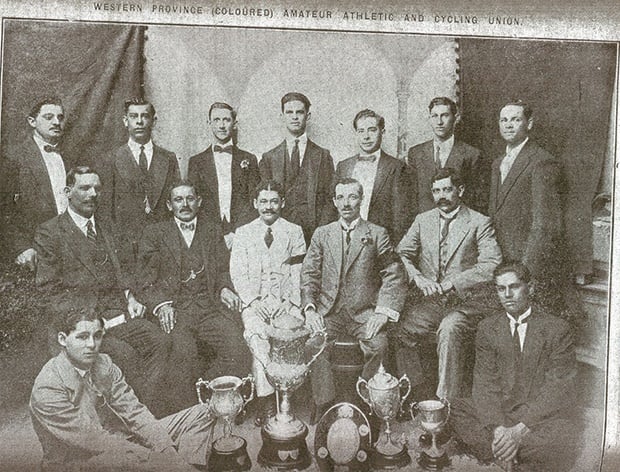

As middle-class people at the start of the 20th century became alert to the problems of poverty and disease in their midst, lurid descriptions of slum life found fashion in the press. This middle classes found the establishment of sport unions a suitable means to allow working-class individuals into their cultural circles but on their terms. It is therefore not surprising that the Western Province Amateur Athletic Association (coloured) (WPAACA) was established in 1901, the same year as the outbreak of bubonic plague in Cape Town on 7 February. It might also have been that this association was established to show support for the British war effort at the time.

Nevertheless, the plague left a scar that affected the geo-political landscape, as mentioned by the research-based work, Cape Town in the 20th century, and affected sport development in the 20th and 21st century. The organisers of the WPAACA were also instrumental in establishing the African Political Association (APO). It has been argued that the APO was established by a group of self-styled coloured businessmen who feared that they might suffer the same plight of forced removals that African inhabitants endured in 1901. The social fallout of the 1901 bubonic plague massively effected sport development in Cape Town. People who were classified as African or native, were falsely accused of bringing the bubonic plague to the city and were forcibly removed to a location outside Central Cape Town, Uitvlugt, later renamed Ndabeni.

Thus, when the first athletic meeting of the WPAACA took place at the Green Point Track in June 1902, there were no African participants. This was unlike the athletic and cycling meeting held in 1898 under the auspices of the Good Hope Athletic Club (coloured) where participants came from different ‘racial’ backgrounds. Over time, sport unions such as the Cape Peninsula Football Association (coloured) and the Cape Peninsula Football Association (Bantu) evolved.

Similar divisions existed in rugby and cricket. It might be argued that this segregation was indirectly caused by the institutional segregation measures after the outbreak of the bubonic plague. This WPAACA maintained an image of cultural ‘respectability’ and exclusive coloured identity up until at least the 1930s (perhaps beyond). One of the ways in which they presented cultural respectability to society, was by public display of sympathy for victims of the later 1918 flu epidemic. In this way they kept their distance from the working classes but at the same time could be seen to be showing sympathy for them. There is a parallel here in the present period where particular businesspeople, after amassing wealth, are able to make negligible donations to fight the spread of the Corona virus while still preserving their financial privileges.

The victims of the 1901 forced removals were once again removed to Langa township in 1927 to make way for a prestigious middle-class suburb called Pinelands, the first ‘whites-only’ garden town in Cape Town. After 1948, the Apartheid regime continued with a forced removal programme that targeted people of colour throughout the 20th century. People were placed in unsanitary conditions with no decent housing, sewerage, recreation or sports facilities.

After 1994, the government adopted neo-liberal economic policies that preserved a cheap labour force. Informal housing settlements sprung up around Greater Cape Town and existing ones expanded that mirrored the social conditions of Ndabeni and Langa. These settlements such as Blikkiesdorp near Delft, Khayelitsha, and others have minimal, if any, decent health care facilities and dismal if not non-existent sports programmes compared to the middle classes and super rich who reside a few minutes’ drive away. As in the early 20th century, because of the outbreak of disease, the 21st century ruling elite have also become aware of the presence of the socio-economic poor among them and are hastily trying to enforce measures to curb the spread of corona virus.

International and national sport federations and the United Nations (UN) Sport and Development for Peace programmes could consider that sport development is more than conjuring dreams of peace and unity. There is a messy historical underbelly, worthy of research funding, that needs to be exposed in order to promote equality, peace and tolerance. This will contribute largely to the UN’s longstanding ideal which claims: “Sport is also an important enabler of sustainable development. We recognise the growing contribution of sport to the realization of development and peace in its promotion of tolerance and respect and the contributions it makes to the empowerment of women and of young people, individuals and communities as well as to health, education and social inclusion objectives."

However, if uncomfortable past historical narratives are left out of future Sport for Development and Peace programmes, cultural and social injustices in sport will remain only to be glaringly exposed by future pandemics and (un)expected disasters. Perhaps this is something that we should also pay attention to as we celebrate the International Day of Sport for Development and Peace (6 April). After all, as Noam Chomsky warned us, we will resolve the corona crisis but the next human made pandemics that result from nuclear war and global warming will be unresolvable. We have to forego a longing for a return to a neo-liberal economic world order, we call ‘normal’. As we have seen, the ‘normal’ was plagued by stigmatisation that bred social viruses in sport and beyond, leaving cultural and social injustices in sport undetected.

Dr Francois Cleophas is a senior lecturer in the Department of Sport Science in the Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences at Stellenbosch University.

Disclaimer: Sport24 encourages freedom of speech and the expression of diverse views. The views of columnists published on Sport24 are therefore their own and do not necessarily represent the views of Sport24.

Publications

Publications

Partners

Partners